I’ve been following the work of activist artist Gianluca Costantini for years. There was a recent exhibition of his art in Bologna of his work of the past twenty years. I’m glad he shares much of his work under Creative Commons licensing, so we can share it.

Hosted in the prestigious Palazzo d’Accursio, overlooking Piazza Maggiore, it brought together all the organizations that have collaborated with me over the years on various human rights campaigns.

“Ceasefire 2005-2025: Twenty Years of Battles for Human Rights“, curated by Lorenzo Balbi, celebrated more than twenty years of art as testimony and activism. With a direct and distinctive line, drawing has become a tool for civil resistance—giving a face and a voice to the fight for human rights, social injustice, and stories too often forgotten.

Set in the evocative Sala Ercole, the exhibition retraced some of the most emblematic campaigns of my journey: from the now-iconic portrait of Patrick Zaki, which became a symbol of international mobilization, to my work with PEN International on imprisoned journalists in Eritrea, and the illustrations created for the “Woman, Life, Freedom” campaign in support of protests in Iran.

Ceasefire 2005-2025: Twenty Years of Battles for Human Rights. The major exhibition in Bologna dedicated to my work over the past twenty years on human rights has just come to a close. It was an important exhibition—one that came from the hear by Gianluca Costantini, Channeldraw, Apr 08, 2025

This is a place of work. If you are not working, then get on the streets and rebel.

Gianluca Costantini

GIANLUCA COSTANTINI: DRAWING AS TESTIMONY

Text by Lorenzo Balbi

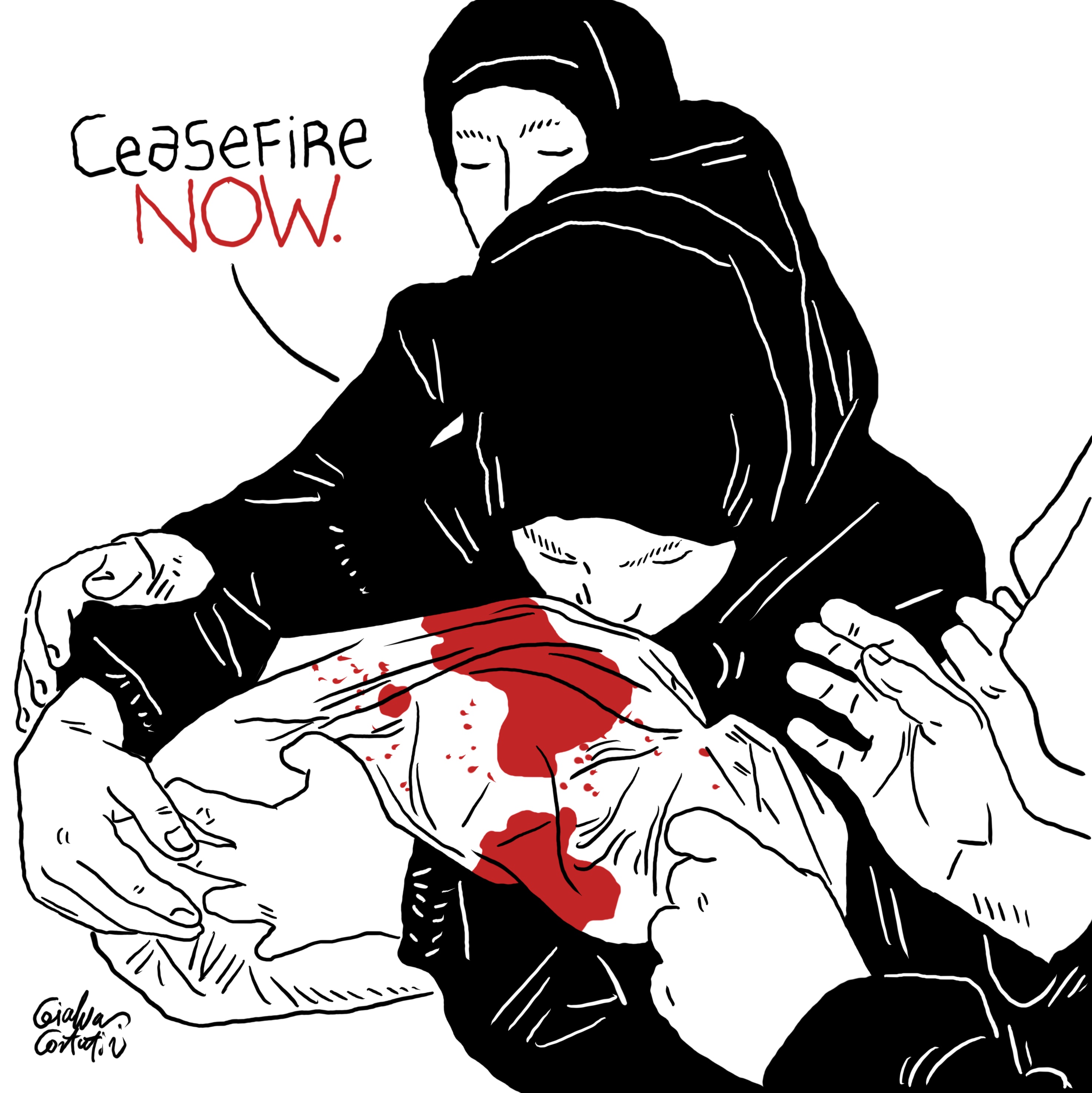

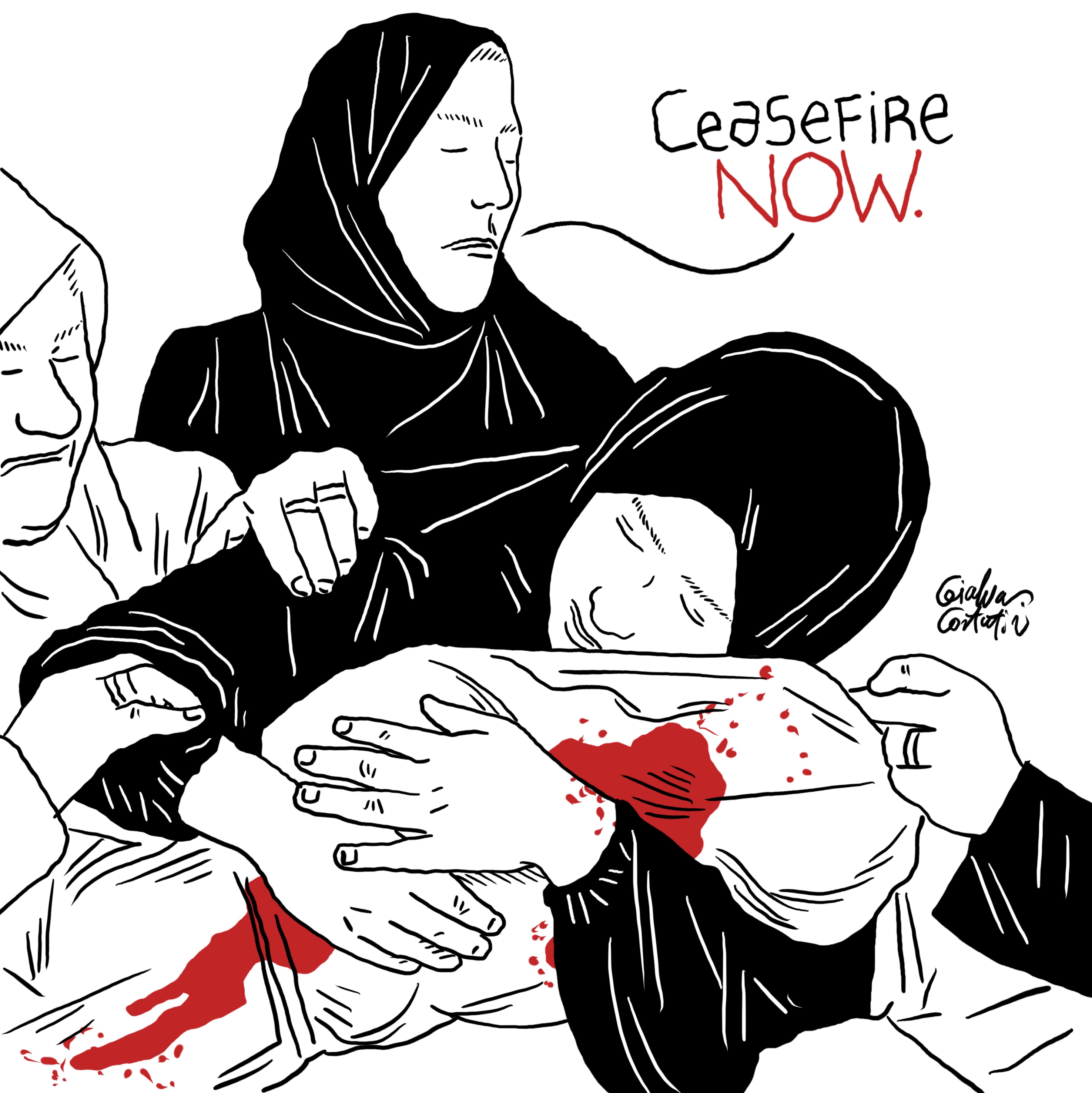

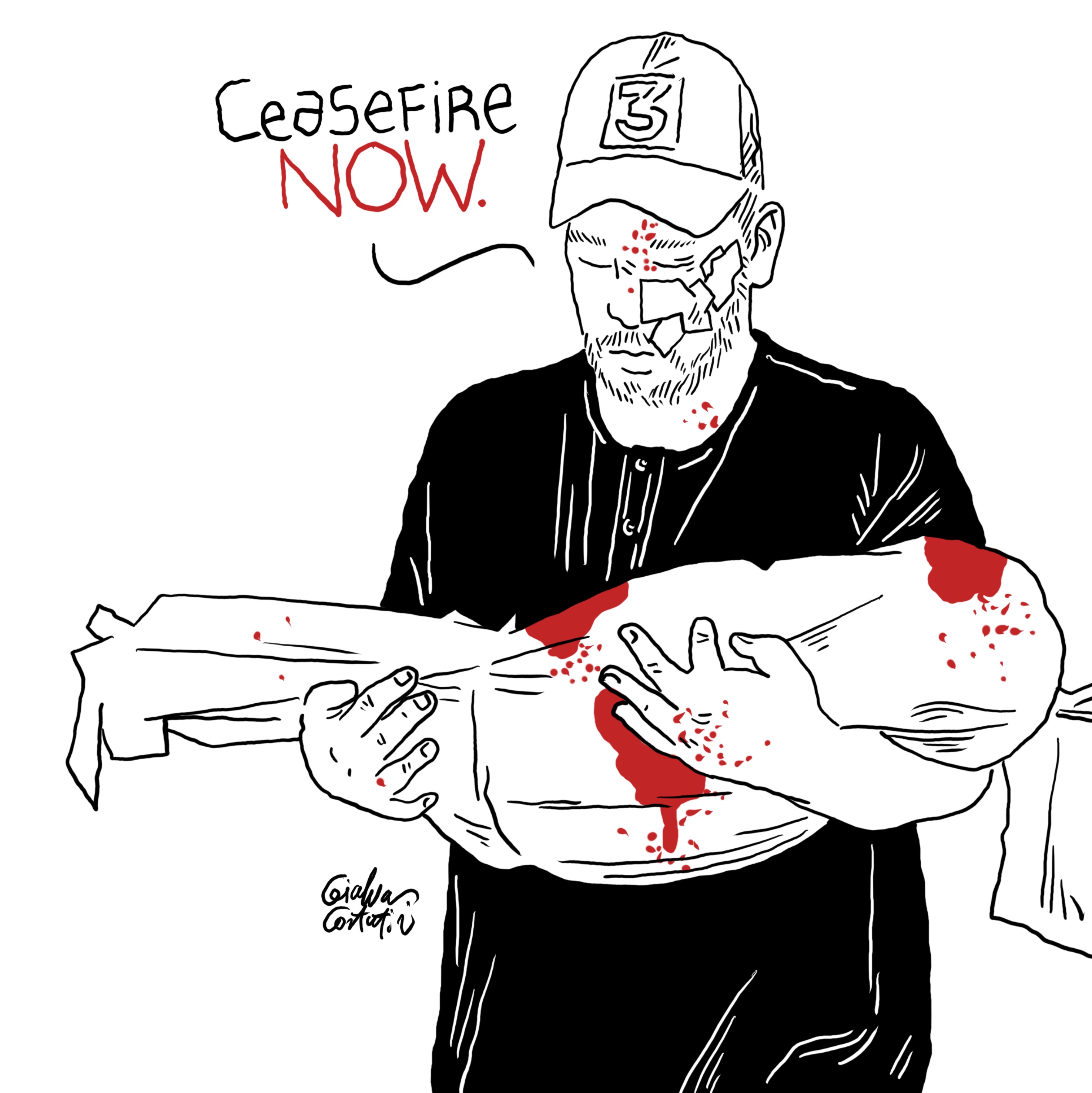

The exhibition dedicated to Gianluca Costantini celebrates more than twenty years of an art form that becomes both testimony and activism. Through the incisive line of his illustrations, Costantini has transformed drawing into a tool for civil resistance—giving face and voice to human rights struggles, social injustices, and stories too often forgotten.

The exhibition traces his artistic commitment through the campaigns that have defined his journey. Among them, the one for Patrick Zaki stands out: the portrait of the Egyptian activist and researcher, created shortly after his arrest in 2020, became a symbol of the international mobilization for his release. The original artwork, now part of the collection at MAMbo – Museum of Modern Art of Bologna, is a powerful reminder of art’s ability to keep public attention alive.

The exhibition’s key image and title refer to Palestine—specifically to Rahaf Ziad Abu Suweirh, a young Palestinian girl who died of a heart attack after a bombing. With the delicacy of his line, the artist conveys both the fragility and the horror of war, turning a personal tragedy into a universal symbol of grief and resistance. Rahaf’s face becomes a silent warning, an invitation to reflect on injustice and the devastating impact of conflict on the most vulnerable.

Gianluca Costantini is not only an illustrator but an activist who uses drawing as a peaceful yet powerful weapon. His works, shared across the globe and often at the center of political controversy, prove that art can be action, resistance, and memory. This exhibition is a journey through his tireless pursuit of truth and justice—a testimony to how images can become a collective cry for freedom.

GIANLUCA COSTANTINI: DRAWING AS TESTIMONY

Text by Lorenzo Balbi

This is a place of work. If you are not working, then get on the streets and rebel. Gianluca Costantini

This is one of Costantini’s drawings in a post that also includes video from Rifaat Radwan, a Palestinian paramedic, who was one of fifteen first responders killed by the Israeli Defense Forces, who buried the bodies and crushed ambulances in a grave. I wrote about this, 15 first responders killed.

Social Drawing

Text by Gianluca Costantini

It’s morning, with its blue stamped up high, and my eyes that won’t open, after a peaceful night of hazy dreams. The light always sneaks in through the windows and whitens the walls of my house as if it wants to clean them. I move around the house, having breakfast while a dog stares at me from the couch. There is never anyone in the house in the morning; everything is still, and my provincial city is serene. Not far from here, it is not the same, and I always feel connected to the unstable world: but it hasn’t always been this way.

BEFORE I grew up in a family with very modest economic conditions, without any political, intellectual, or artistic education. Although it’s cliché to say, art saved me. Around the age of seventeen, art became an obsession, wanting to be part of it became a well-defined and selfishly driven goal; it still is. All the unconscious traumas I had suffered in my childhood were healed by the poems of Rimbaud, anesthetized by the drawings of Klimt, and cured by the films of Greenaway. I made new fathers, older cartoonists, and Academy teachers, and I began taking trains to Italian cities. During the early years of the Academy, I established a close relationship with artists and magazines, starting to publish at a very young age. My world was very aesthetic, decorative, full of dreamlike beauty, constantly traveling to escape reality. But little by little, this world cracked, and within me grew a dissatisfaction. Roberto Daolio, an art critic who followed me with interest, once asked me, “Is something wrong?” He had sensed my discomfort; I was stuck, stranded, stranded.

AFTER Then came Sarajevo, in 2001, with its walls pierced by bullets, with its vast cemetery on the hill, with the map for mines. I had been sent by GAI (Young Italian Artists) to the Mediterranean Biennale. The war had just ended, and I had never been in a war zone. Everything changed here. I wandered the streets of the city for days, ignoring the Biennale appointments and my traveling companions. Everything struck me—the glances, the children, the people living in houses without walls, where you could see their daily intimacy.

I came back home with a heavy emotional baggage, and the following month I left for Istanbul. I had changed, and I had to see the world I was drawing. A few years later, I began organizing events with Elettra Stamboulis in Ravenna, my city. We started with Joe Sacco, the famous Maltese cartoonist, and continued with Aleksandar Zograf and Marjane Satrapi. We didn’t stop for more than fifteen years organizing and, most importantly, getting to know each other. These authors, a few years older than me, unknowingly instilled new ideas and energy in me. One day, by chance, I flipped through a book by the German photographer Ernst Friedrich, “War Against War,” a photographic book with short captions shedding light on the consequences of World War I, intending to show the true face of war (wounded, mutilated, executions, suffering, misery, and death). This book gave me the idea to create political drawings with text on them, and to do so, I completely changed my drawing style, abandoning everything I had done in the previous ten years.

Ceasefire 2005-2025: Twenty Years of Battles for Human Rights Text by Gianluca Costantini

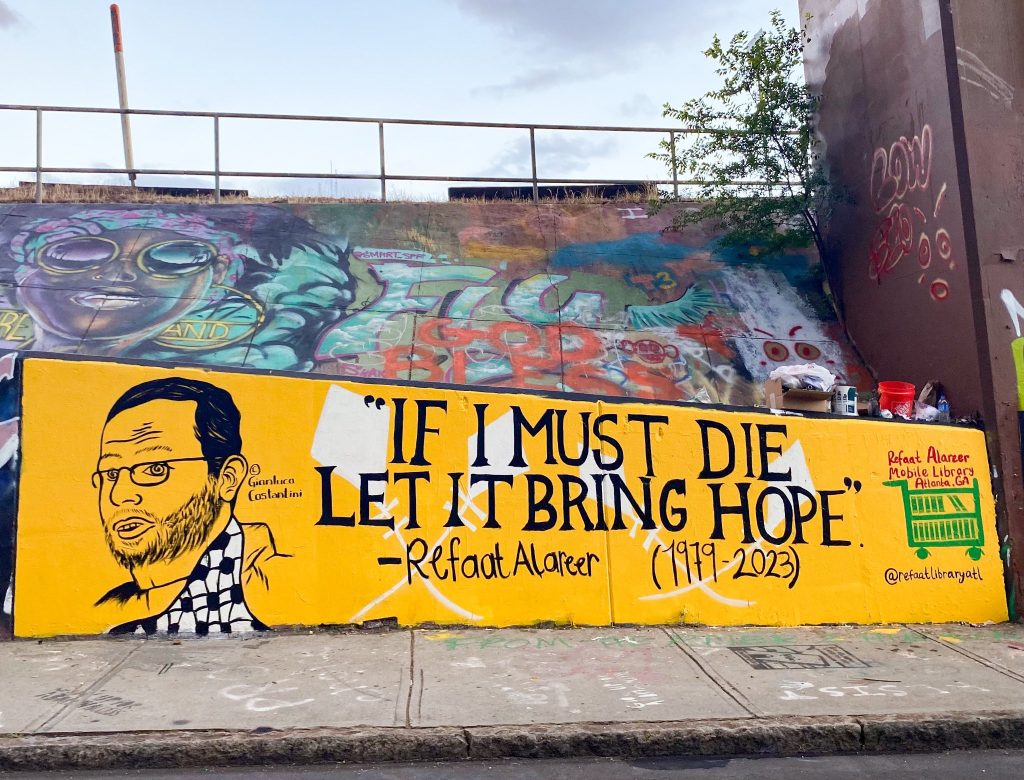

This is a mural in Atlanta, Georgia, with Gianluca Costantini’s drawing of Refaat Alareer, a Palestinian poet who was targeted and killed by Israeli Defense Forces.