Today my small Quaker meeting will gather for our weekly hour of silent worship together.

Several of us no longer live in the Bear Creek community near Earlham, Iowa. So, we have adapted to using an online meeting application (Zoom) to connect us across the distances.

The hour prior to meeting for worship is a time to discuss various aspects of our faith and how we express it in the world. This week’s premeeting will be a discussion about peace and justice concerns.

If you are reading this, you likely know that I passionately believe peace and justice concerns are the expressions of faith in general, and my faith in particular. This was instilled in me as I grew up in the Bear Creek meeting community, at Scattergood Friends School (Quaker boarding high school), and in many different ways as my life unfolded as I’ve been led by my faith.

I often irritate my Quaker Friends and others as I advocate for justice causes I’ve been led to participate in. I try various ways to express why I believe in the causes I do, and I wish others would join me in this work.

I often forget to express, indeed often forget, that I am not asking others to join the justice work I do. Rather, I want others to discern what their faith tells them to do. And then do that.

These realities have hardened society, allowing people to bury their heads and ignore the horrors unfolding across the world. Ferocious disregard for the pain of others has become a way to protect oneself from the inflation of suffering. What can one do with the wretchedness that has come to define life across the planet? What can I do? What can you do? –Vijay Prashad

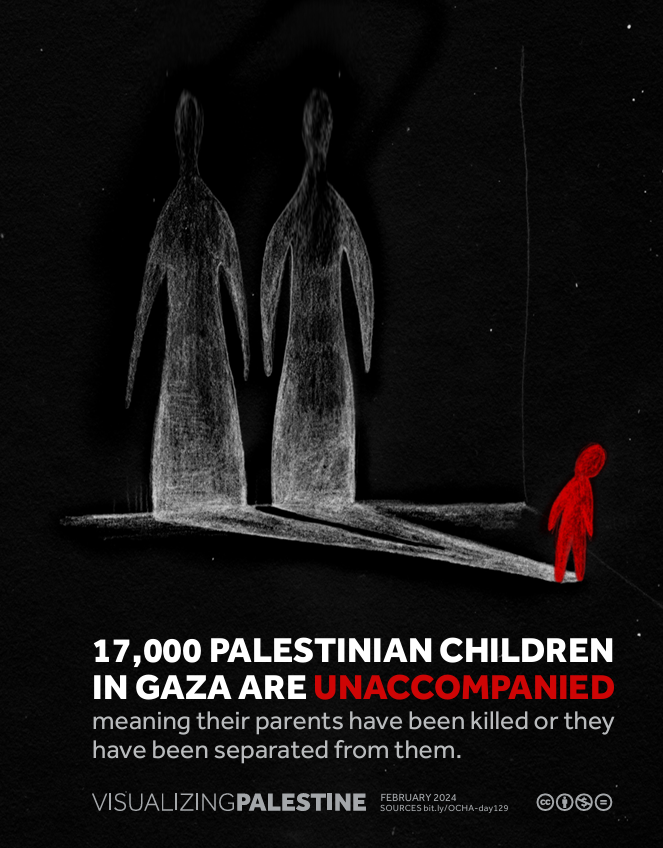

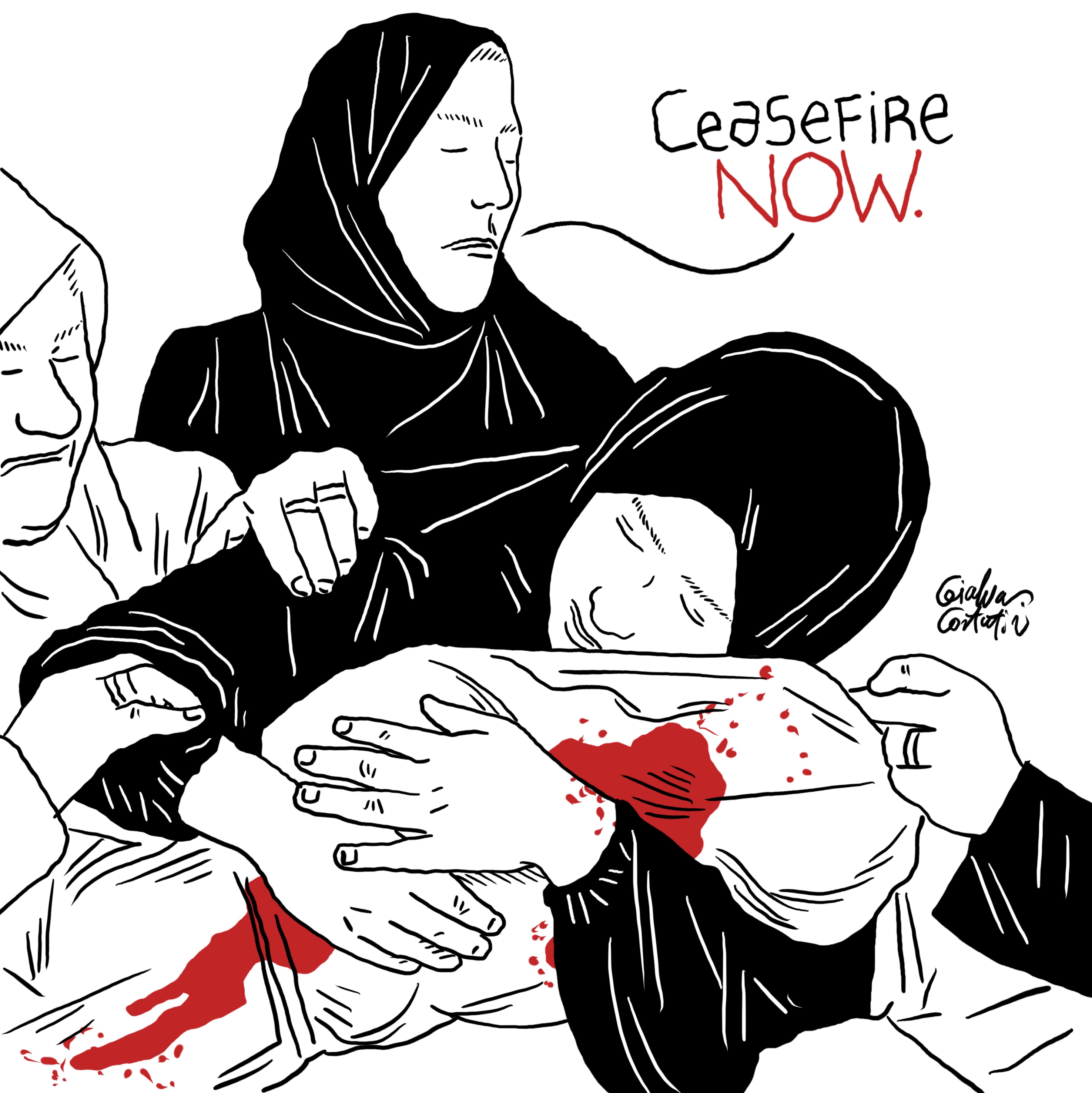

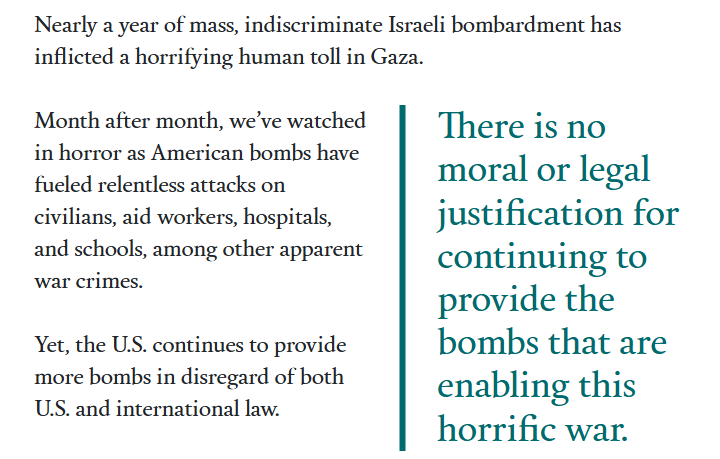

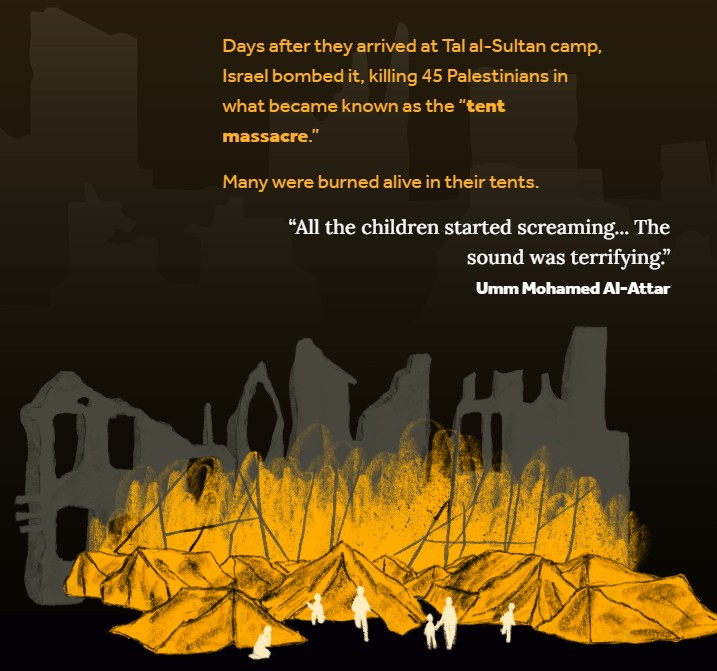

Pain shudders through the arteries of global society. Day after day passes by as the genocide against the Palestinian people continues and the conflicts in the Great Lakes region of Africa and Sudan escalate. More and more people slip into absolute poverty as arms companies’ profits soar. These realities have hardened society, allowing people to bury their heads and ignore the horrors unfolding across the world. Ferocious disregard for the pain of others has become a way to protect oneself from the inflation of suffering. What can one do with the wretchedness that has come to define life across the planet? What can I do? What can you do?

In 2015, the Palestinian poet Dareen Tatour wrote Qawim ya sha’abi, qawimhum (Resist, My People, Resist Them), for which she was arrested and imprisoned by the Israeli state. A poem that can send you to prison is a powerful poem. A state threatened by a poem is an immoral state.

Resist, My People, Resist Them

Resist, my people, resist them.

In Jerusalem, I dressed my wounds and breathed my sorrows to God.

I carried the soul in my palm

for an Arab Palestine.

I will not succumb to the ‘peaceful solution’,

never lower my flags

until I evict them from my homeland

and make them kneel for a time to come.

Resist, my people, resist them.

Resist the settler’s robbery

and follow the caravan of martyrs.

Shred the disgraceful constitution

that has imposed relentless humiliation

and stopped us from restoring our rights.

They burned blameless children;

As for Hadeel, they sniped her in public,

killed her in broad daylight.

Resist, my people, resist them.

Resist the colonialist’s onslaught.

Pay no mind to his agents among us

who shackle us with illusions of peace.

Do not fear the Merkava [Israeli army tanks];

the truth in your heart is stronger,

as long as you resist in a land

that has lived through raids and victory.

Ali called from his grave:

resist, my rebellious people,

write me as prose on the agarwood,

for you have become the answer to my remains.

Resist, my people, resist them.

Resist, my people, resist them.

‘Hadeel’ in the poem refers to Hadeel al-Hashlamoun (age 18), who was shot dead by an Israeli soldier on 22 September 2015. This murder took place alongside a wave of shootings – many fatal – against Palestinians by Israeli soldiers at checkpoints in the West Bank. On that day, Hadeel came to Checkpoint 56 on al-Shuhada Street in Hebron (Occupied Palestinian Territory). The metal detector beeped, and the soldiers told her to open her bag, which she did. Inside was a phone, a blue Pilot pen, a brown pencil case, and other personal belongings. A soldier yelled at her in Hebrew, which she did not understand. Thirty-four-year-old Fawaz Abu Aisheh, who was nearby, intervened and told her what was being said. More soldiers arrived and aimed their guns at both Hadeel and Fawaz. One soldier fired a warning shot and then shot Hadeel in the left leg.

At this point, a soldier, claiming he saw a knife, fired several shots into Hadeel’s chest, who was photographed standing still moments before. After being left on the ground for some time, she was taken to a hospital, where she died of blood loss and multi-system failure resulting from the gunshot wounds. Human rights organisations such as Amnesty International and B’Tselem said that the question of the knife was moot since Hadeel had been the subject of an ‘extrajudicial execution’ (let alone the fact that testimonies about the knife were inconsistent). Tatour’s depiction of Hadeel’s execution in broad daylight is a powerful reminder of the waves of violence that structure the daily lives of Palestinians.

A month after Hadeel was killed, I met a group of teenagers in a refugee camp near Ramallah. They told me that they see no outlet for their frustrations and anger. What they do see is the daily humiliation of their families and friends by the Occupation, which drives them to desperation. ‘We have to do something’, Nabil says. His eyes are tired. He looks older than his teenage years. He has lost friends to Israeli violence. ‘We marched to Qalandiya last year in a peaceful protest’, Nabil tells me. ‘They fired at us. My friend died’. Colonial violence bears down on his spirit. Around him young children are executed with impunity by the Israeli military. Nabil’s body twitches with anxiety and fear.

Resist, My People, Resist By Vijay Prashad, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. December 27, 2024