Nonviolent protest pre-dates the 1960s, but that is where my experiences began.

In 1969 I was a high school student at Scattergood Friends School, a Quaker boarding school, where most of us opposed the Vietnam War. We organized a draft conference at the school (see agenda below).

During the Oct. 15, 1969, National Moratorium for the End of the War in Vietnam, the entire school (65 students) walked from the school to the University of Iowa (12 miles), holding peace signs and participating in the antiwar activities there.

From the school committee minutes:

A group of students attended Committee meeting and explained plans for their participation in the October 15 Moratorium. The Committee wholeheartedly endorses the plans. The following statement will be handed out in answer to any inquiries: “These students and faculty of Scattergood School are undertaking the twelve mile walk from campus to Iowa City in observance of the October 15 Moratorium. In order not to detract from the purpose of the walk, we have decided to remain silent. You are welcome to join us in this expression of our sorrow and disapproval of the war and loss of life in Vietnam. Please follow the example of the group and accept any heckling or provocation in silence.”

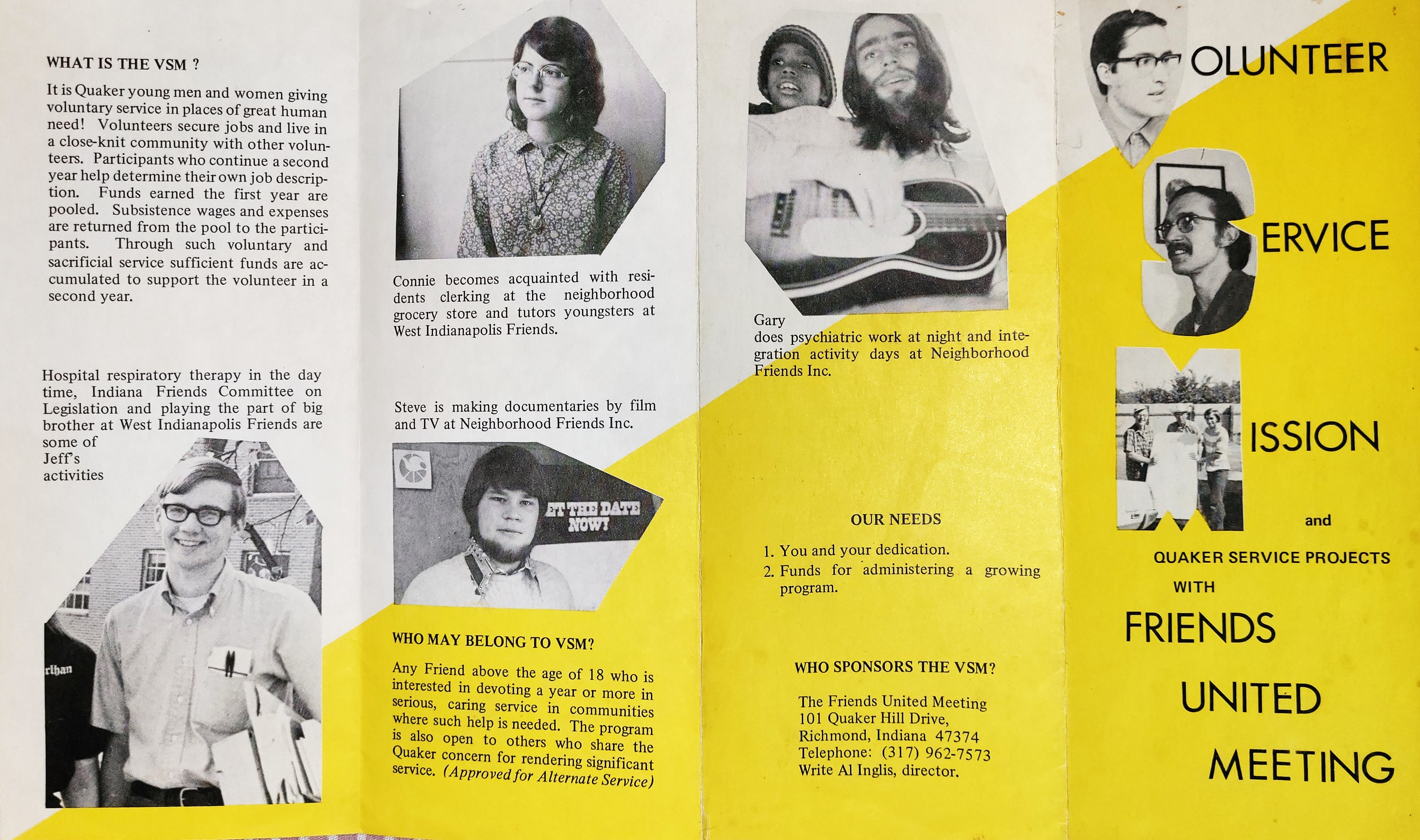

(This is one of the first photos I developed as I was learning to use the darkroom at Scattergood.)

In 1968, hundreds of students at Columbia University occupied five buildings. The students barricaded themselves inside the buildings for a week to protest the university’s military ties as part of a broader anti-Vietnam War movement.

Then, the university called in the NYPD. What followed was one of the largest mass-arrests in New York City history. NYPD officers arrested 700 students, many violently. More than 150 students were hospitalized. In the aftermath of these arrests, Columbia’s leadership went on to create policies designed to ensure that what happened on April 30, 1968 would never happen again and that students’ right to non-violent protest would be protected.

But Columbia tarnished that commitment when the school’s President Nemat “Minouche” Shafik asked the NYPD to dismantle an encampment of students who had set up tents on the university’s lawn. More than 100 students were arrested.

As Juan Gonzales — who was one of the leaders of the 1968 protests — noted, this time the university acted against the protesters even more quickly than they did 56 years ago.

“I think what is really unusual about this process is that here the university moved in very quickly, and also these students were not disrupting classes,” Gonzales said on “Democracy Now!” “We occupied buildings. We did not allow classes to go forward in 1968. So, the disproportionate nature of the response of the university, the quickness with which it responded, without even consulting or listening to the faculty, is really astounding.”

New Yorkers should be able to express their views on Israel and Palestine without having to fear becoming a target of the NYPD or a victim of police abuse. Students non-violently demonstrating should never face down a baton or a gun.

Our history shows us that non-violent debate is good for society, and that it shouldn’t be snuffed out by police – especially not on campus.

Pro-Palestine Campus Protests Shouldn’t be Snuffed Out by Police. Our history shows us that non-violent debate is good for society by Donna Lieberman, NYCLU, ACLU of New York, May 2, 2024