Monday, July 22, 2024, was the final day of this journey. I had been staying in the cottage at the Bear Creek meetinghouse, near Earlham, Iowa. I left Sunday afternoon to travel to West Branch. I went to be present for and take photos of the ceremony that was going to occur at the cemetery there. The family said they would like photos to be taken, which I was glad to do for them.

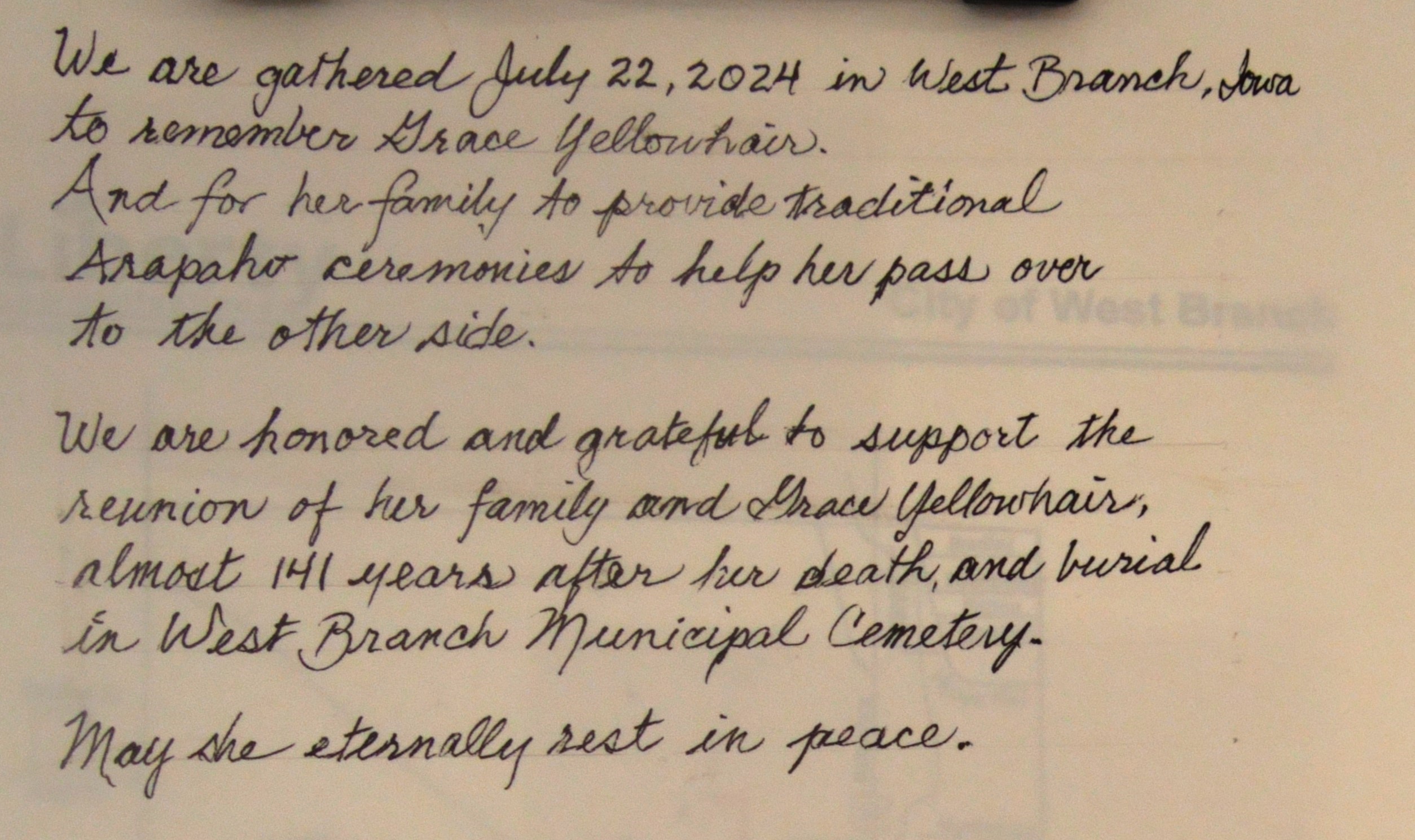

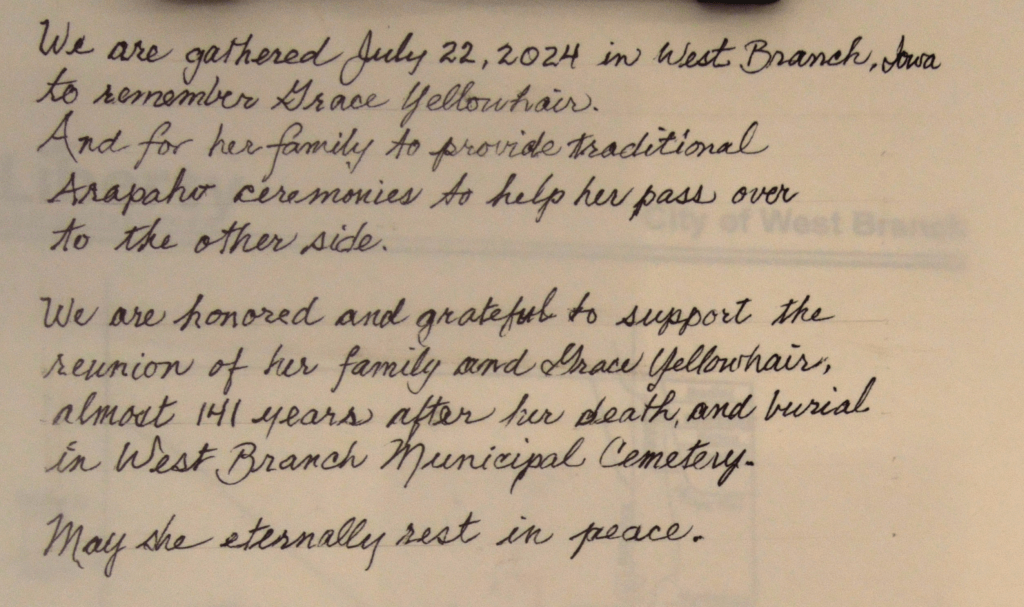

This document, that those who attended had a chance to sign, explains what this is about.

A remarkable series of events unfolded from a research paper by Park Ranger Peter Hoehnle, a National Park Service guide at the Herbert Hoover National Historic Site, who holds a doctorate in history. This is a link to that paper, The West Branch Industrial School.

The Indian boarding school in the town of West Branch was open for a short time in 1883. The Quaker boarding high school I attended, Scattergood Friends School and Farm, is located just two miles East of West Branch, so I’m familiar with the town.

Many Quakers today are deeply troubled by the history of the Indian Boarding Schools. Quakers were involved in the efforts to assimilate native children into the culture of the settlers. They thought this would be helpful in light of the flood of settlers moving across the land.

From Peter’s paper:

The boarding school movement grew from the so-called “peace policy” pursued by President Ulysses S. Grant’s administration in the 1870s. A key component of this policy, advocated by members of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) was Grant’s appointment of Quakers to positions of authority in Native American policy. Among the Quakers who took an active interest in Native American rights were several members of the West Branch community, particularly members of the extended Miles family. Benjamin Miles, the head of the family, was an Ohio native, who arrived in West Branch, a widower with children, in 1856. Two years after arriving, Miles married Elizabeth Bean, whose brother, Joel, became a prominent figure in the evangelical/ progressive doctrinal split of the Quakers in the 1880s. Elizabeth Miles was a graduate of the Rhode Island Friends Boarding School, and often served as a clerk in the West Branch Quaker meeting.

In 1868, the Miles family moved from their farm to a home in the village of West Branch.

Peter Hoehnle, The West Branch Industrial School

From our vantage point today, we know that forced assimilation amounted to cultural genocide and was a grave injustice. We also know terrible abuses, some leading to deaths, commonly occurred in many of those institutions. The remains of thousands of children buried at those institutions have been and continue to be found using ground-penetrating radar.

There are many ongoing Quaker efforts to discover more of this history and consider how to respond today. Although the local community was familiar with the history of the school, I had not been aware of it, so I’m grateful for Peter’s research. Peter was at the ceremony.

The school opened on January 16, 1883. In addition to Benjamin and Elizabeth Miles, the staff included teachers, Miss Jennie Crosbie, and Sina Ann Branson, who oversaw the culinary department. By arrangement with the government, Mr. and Mrs. Miles were paid $167 per year “for the keep of each Indian boy or girl sent to the school.

Peter Hoehnle, The West Branch Industrial School

My friend and member of the West Branch Quaker meeting, Judy Cottingham, contacted me when she discovered Peter’s paper, because she knew of my interest and concerns related to Indigenous peoples.

I contacted my friend, Paula Palmer, whose ministry is related to Quakers and the Indian Boarding Schools. She, also, had not known about the West Branch school.

One of the many things we learned from Peter’s paper was of the deaths of two students at the school, and their burial in unmarked graves in the West Branch Municipal Cemetery.

Death of Grace Yellowhair

A particularly unfortunate consequence of the boarding schools was that a significant number of the children enrolled in them succumbed to disease and died. In many cases, the students were exposed to diseases for which they had no natural immunity. In charitable schools of this type, it would also not have been uncommon for students to use the same wash water. Further, living in a converted store building, as they did, there is a high probability that sanitary systems were simply inadequate. The students at the West Branch school were no exception, unfortunately. On June 15, 1883 – A student at the school, who was approximately eight, died of “malaria fever,” and was buried in an unmarked grave in the Quaker section of the West Branch Cemetery. The West Branch Local Record reported the death: “Friday morning, June 15th, 1883, of malaria fever, after lingering several weeks, THEADORE ROGERS, aged 8 years. This little boy was a member of the Indian Industrial School at this place, bright and industrious for one of his age, cheerful though quiet in disposition. He bore up under his affliction with remarkable courage, His mother and stepfather, members of the Osage tribe reside in the Indian Territory. The funeral occurred Saturday at 10 A.M. from the Friends’ Church.”

A second death, that of Grace Yellow Hair, from the Arapaho Nation, occurred on September 11, 1883 –She was fifteen years old and had suffered a lingering illness for two months. Her illness is diagnosed as malaria. She had arrived at the school in mid-March. She was buried next to Theodore Rogers in the West Branch Cemetery. Her grave, likewise, remains unmarked.

(See West Branch Local Record of September 13, 1883; Bears, Buildings in the Core-Area, 269.)

Peter Hoehnle, The West Branch Industrial School

Paula Palmer knows Frank MedicineWater who is the Cheyenne-Arapaho tribal officer trying to identify the Cheyenne and Arapaho students who attended boarding schools and trace their descendants. She sent him the article about the Quaker schools for Cheyenne and Arapaho in Indian Territory.

Frank MedicineWater must have contacted Fred Mosqueda, the Arapaho Language and Culture Program Outreach Specialist Coordinator for the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma, who wrote:

Thank you very much for this information. I am very interested in obtaining information of the Arapaho girl, Grace Yellowhair, and the whereabouts of the cemetery. My wife was raised partially by her Grandfather, Gustave Yellowhair. I am sure I can trace lineage to Grace. Thank you again.

–Fred Mosqueda

Iowa Quakers

When we heard about this, Judy and I felt moved to do something. It didn’t matter that our yearly meeting, Iowa Yearly Meeting (Conservative), was not involved with the school, as far as we can tell. I did tell our Yearly Meeting clerk about this. Judy invited West Branch Friends Church to participate in the events.

Judy continued correspondence with Fred, in particular about his desire to come to the gravesite. Judy also did research to find the unmarked plots where Grace Yellowhair and Theodore Rodgers, Osage, were buried near each other in the Friends’ section of the West Branch Municipal Cemetery. Before the gathering Monday, white flags had been placed at the site by city staff to mark their location.

The family did not want to disinter Grace’s remains. But they felt it necessary to come to the gravesite to perform the ceremonies that would allow Grace to pass over to the other side. Since that had not been done before, her spirit could not leave. With the ceremony, her spirit was finally set free.

The ceremony was held Monday, July 22nd, at the gravesite of Grace. The Yellowhair family included Theodore Rodgers, Osage, in the prayers to assist him too in passing to the other side. The family did not want a public event. I’m very glad I was able to attend the powerful ceremony. Among the others attending were Judy and her husband Jim Cottingham, a number of members of the West Branch Friends Meeting of Iowa Yearly Meeting (Conservative), West Branch Friends Church, and guests including Peter Hoehnle, and the West Branch mayor.

Traveling from Oklahoma to attend the ceremony with Fred Mosqueda were his wife Mary Fletcher, and John Fletcher, Mary’s brother.

As we were waiting, I noticed Fred slowly moving through those gathered, greeting each one.

Fred began by explaining what was going to happen. First he gave an oral history of why Indian children were forced to attend what were called Indian Boarding, Residential or Industrial schools.

It was striking to hear stories about these schools from an Indigenous perspective. Fred spoke of the US Army killing all the buffalo, so the native people would be confined on small reservations. Because there was a provision that allowed the native people to hunt buffalo wherever they found them.

He told of families having no choice but to allow their children to be taken to the Indian schools, or they would no longer receive food and other supplies from the government.

Cedar was burned and feathers used to fan the smoke. Fred sang three songs with the drum he brought. These allowed Grace’s spirit to finally leave, and cross to the other side.

We stood in silence as a group to witness this powerful ceremony. I strongly felt the presence of the Spirit.

We then went to the West Branch Friends Meeting, where we enjoyed a potluck lunch together. The meal was also part of the traditional ceremony—it was the last meal Grace shared with her family on earth. They made up a plate of food for her, and it was set outside in a sheltered spot.